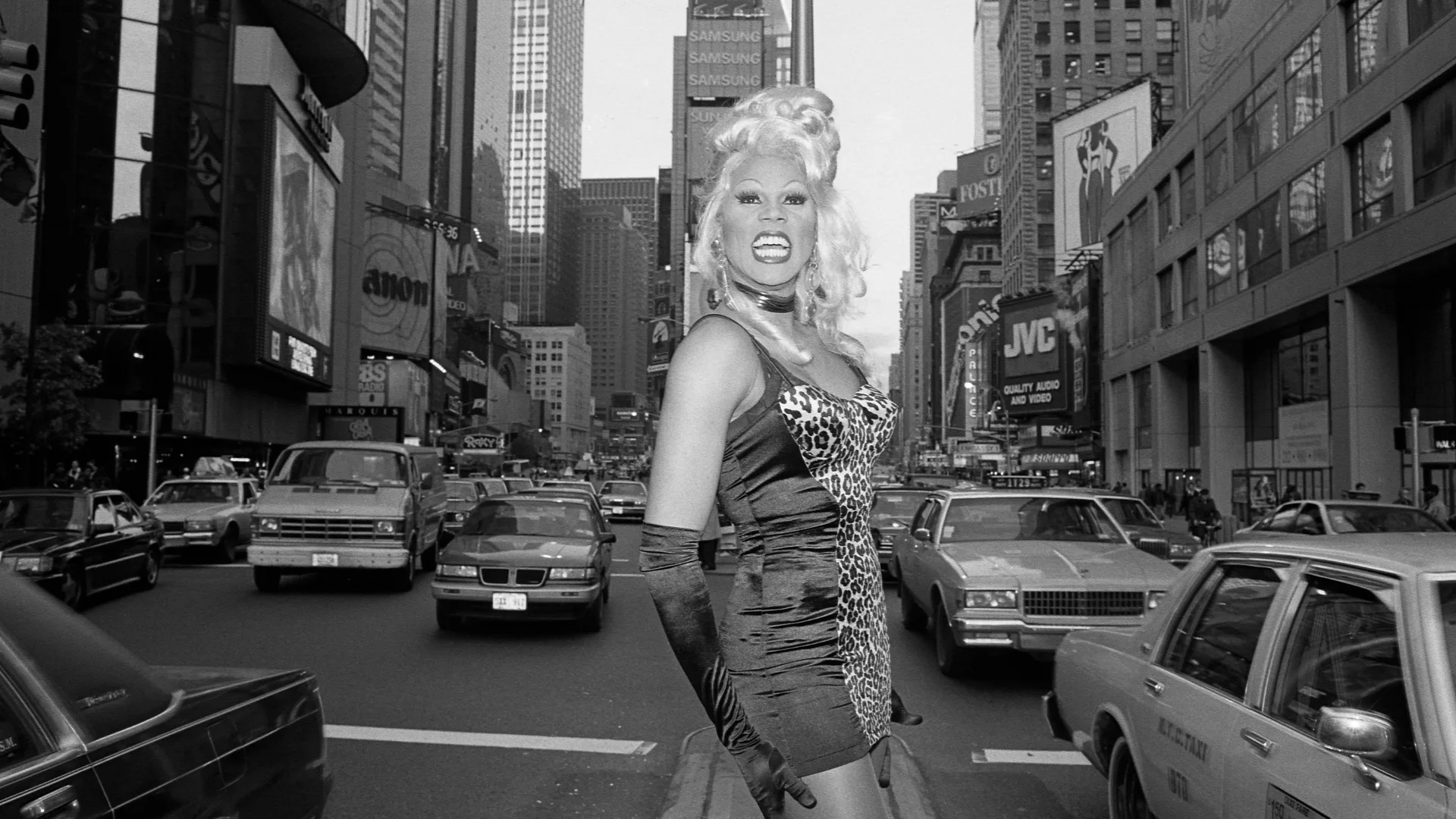

Did someone say cheese and pineapple? The Barbican are going back in time, with a film season dedicated to Queer cinema of the 1970s. Queer 70s: LGBTQ+ Cinema in the Decade after Stonewall is a poetic theme for Britain’s most famous brutalist building, but this programme is anything but hard and functional. Rather, it’s an unexpected reveal of a lush Queer world. Decriminalised in an increasing number of countries and US states at the time, LGBTQ+ culture began to thrive in the wake of the Stonewall riots of 1969.

“These riots didn’t just trigger the birth of Pride in America, but you started to see resistance and demands for equality burgeoning throughout the world,” says programme curator Alex Davidson. “This is reflected in cinema.”

The 70s represented a unique era of tentative Queer optimism in art, before the tragedy of the AIDS epidemic took hold in the 1980s.

“One of the things I really wanted to avoid was going into these narratives of tragic Queer characters,” says Davidson. “Happy endings are so rare in Queer cinema, [that was the case] even until fairly recently. But in the 70s you started to have these very moving, lovely endings for Queer characters, and there was hope, and there was power.”

For Davidson, this all comes down to perspective. “A tragic narrative, or a flawed Queer character, is still a very interesting one at this time. I wanted to show, as much as I could, LGBTQ people behind the films telling these stories themselves, as opposed to a heterosexual white male director.”

Of course, the 1960s was a time of great momentum for various socio-political movements, not just LGBTQ+ rights. The fight for civil rights, feminism, anti-censorship and counter-culture all coalesced to create an intersectional, liberal environment for Queer film to flourish in the subsequent decade. The festival opens with the feminist Lesbian short films of Barbara Hammer, Dyketactics (1974), Superdyke (1975), Women I Love (1976) and Double Strength (1978). “In the 70s, suddenly you had these very joyful lesbian, experimental films… They’re very sex positive, and they’re full of nudity. It’s an 18+ programme!”

Sex positivity is a big part of the season in fact. One of the films, Adam & Yves (1974), is an actual porno. “There was this sort of ‘porno chic’ movement happening in the 70s,” Davidson points out. This was at a time when porn would be viewed in an adult cinema, not on a video tape or phone screen, which made the cinemas a valuable means of meeting other people in the community. “I chose Adam & Yves because it’s a very artistic film. It’s very poetic, it’s very lyrical. There’s not really another porn film like it, I don’t think.”

Showing porn films made by Gay men is also, obviously, another way of highlighting positive Queer experiences. “[Porn] showed Gay men having a good time. Sometimes, a very good time.”

For the ladies, Davidson has laid on a screening of Chantal Akerman’s seminal film Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974), which features a ten minute Lesbian sex scene, the first of its kind in mainstream cinema. “It’s passionate and it’s unflinching. It doesn’t cut away to a beautiful rose or sonorous music. It is raw f*cking.”

Meanwhile, Davidson also highlights films in the programme that were released in spite of the illegality of homosexuality or gender non-conformity in their country of origin. Particularly interesting is My Dearest Senorita (1972), a film which came out of Franco’s Spain, where homosexual people were highly criminalised and persecuted. “I don’t know how it got made,” says Davidson.

The film depicts an unhappy person, assigned female at birth and femme presenting, struggling to understand why they need to shave and have romantic feelings towards their maid. Their doctor helps them discover a new identity as ‘Juan’.

“It’s a very sympathetic portrayal of an Intersex character, although that word isn’t really used in the film. In this era they wouldn’t use that terminology. But by the end they live as a man and find happiness and love and a happy ending.”

From India, where homosexuality has only been legal since 2018, comes the 1971 film Badnam Basti (1971) (which translates to “neighbourhood of ill repute”), a melodrama about a Bisexual love triangle set in Uttar Pradesh. “It’s not sensationally played. In fact, it’s vey subtly played,” says Davidson. “Even for the next few decades it was very rare in Indian cinema to see this kind of representation, and certainly not with sympathetic characters. It’s a miracle this film exists.”

The breadth and diversity on display in the program is testament to the uniqueness of the Queer experience, and how this can be brought alive through culture. “It’s such a unique exciting era for queer creativity and Queer LGBTQ representation, and I hope that’s come across in the season.”

Queer 70s: LGBTQ+ Cinema in the Decade after Stonewall runs from Wed 11 Jun – Wed 16 Jul 2025 at the Barbican London. Purchase tickets here.